Talk: "Deep Learning in Compilers"

(The following post is the outline for a 10 minute talk I gave at the “PPar Student Showcase”)

My primary research interest is in using machine learning to improve the decision making of compilers. To give you a flavor for the kind of problems I’m interested in solving, I’m going to give a brief overview of two recent publications that I’ve co-authored with my supervisors.

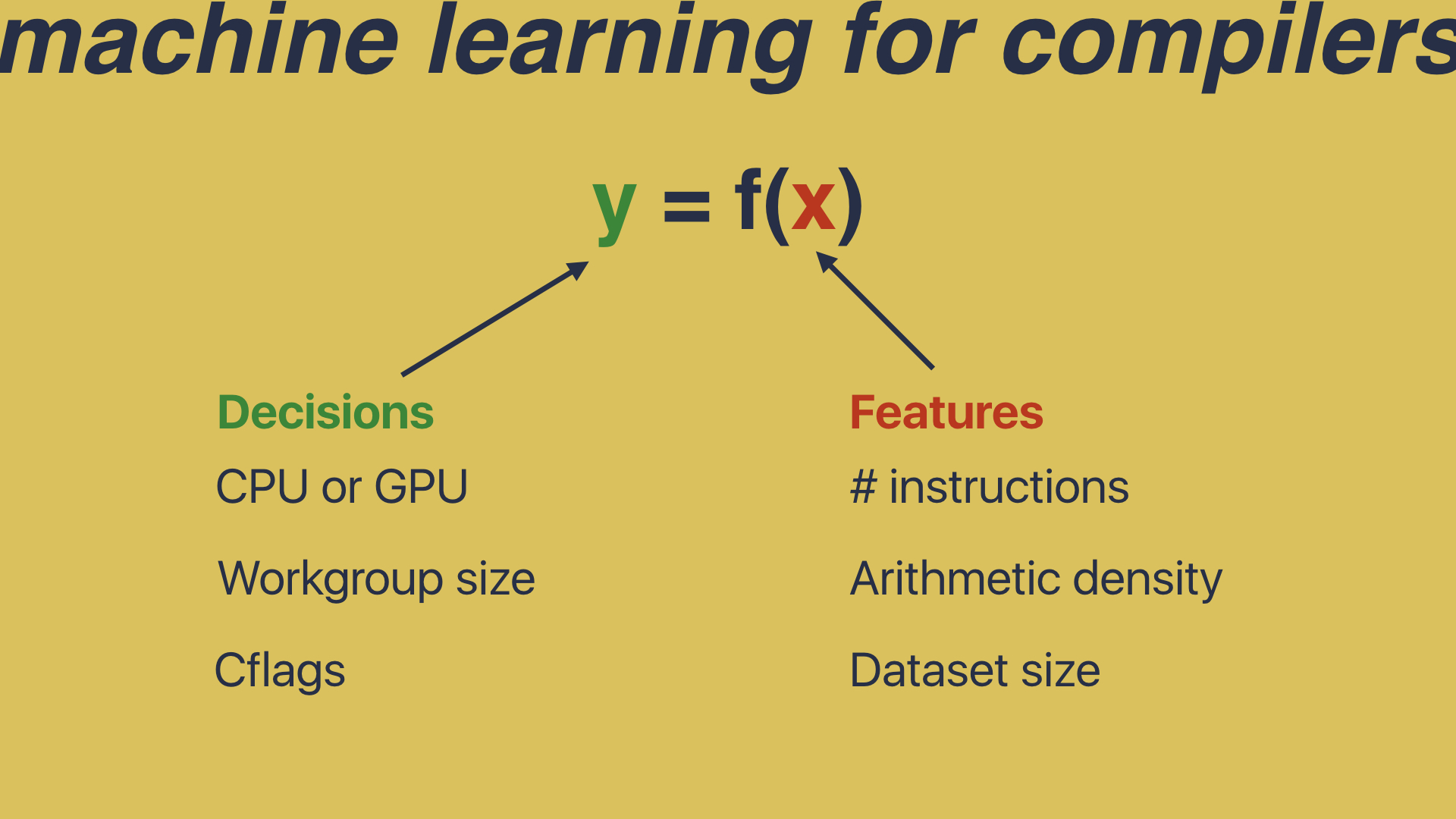

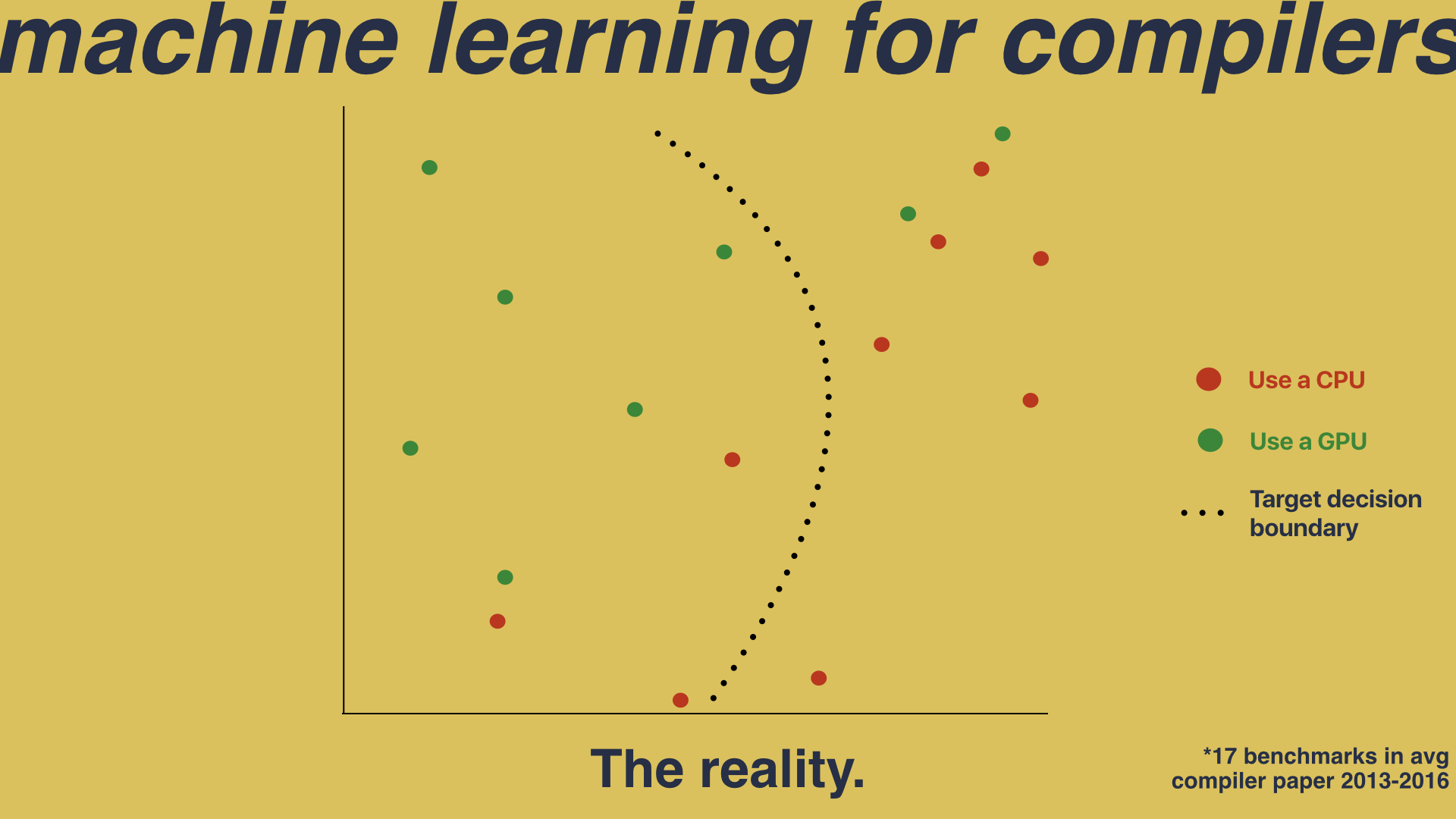

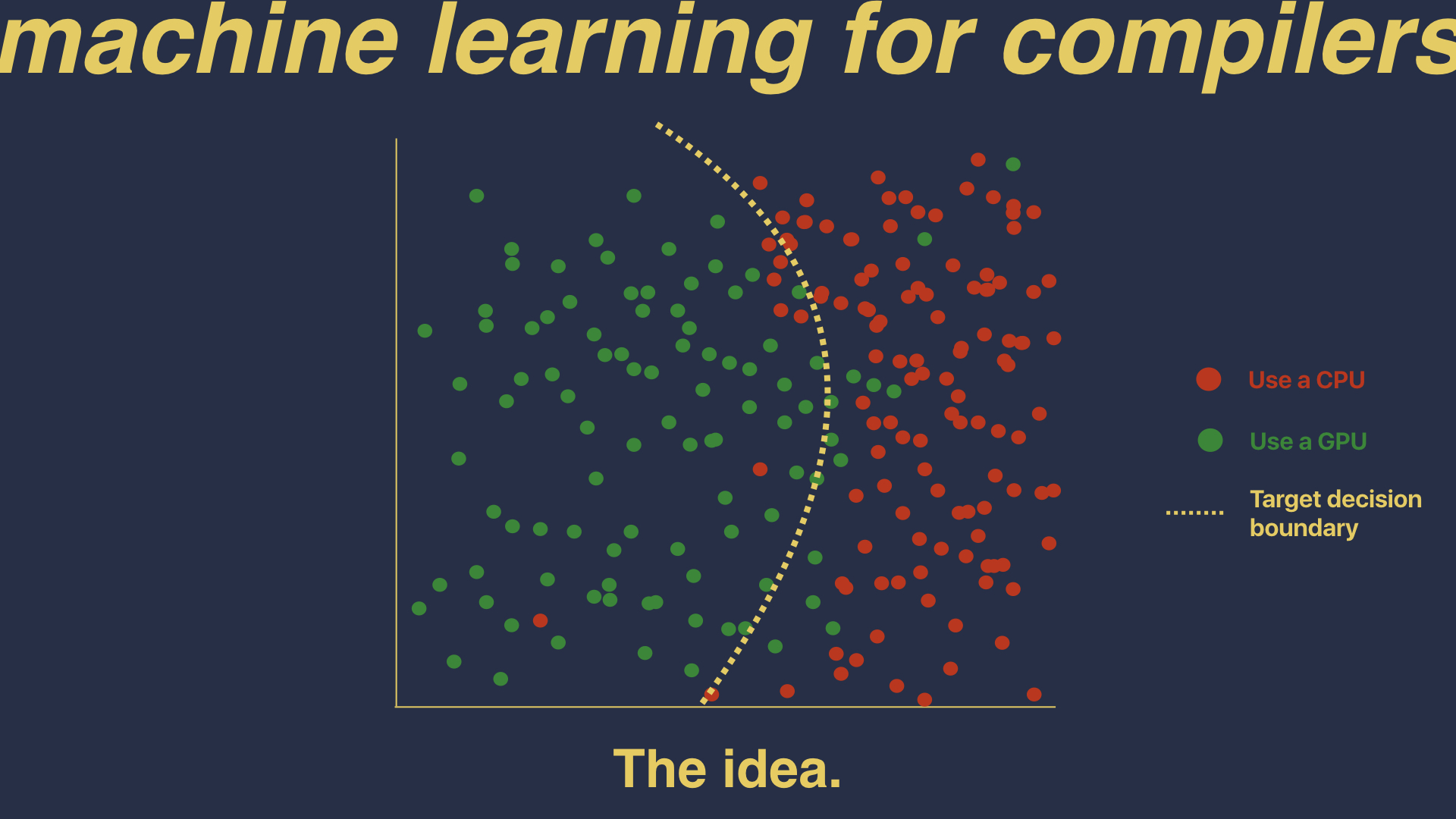

Let’s begin with a definition. For the purpose of this talk, we can treat machine learning as simply y=f(x). That is, it is a system for estimating a function f, so that given a value for x, we can predict a value for y. So let’s say we’re building an optimizing compiler, and we want the compiler to decide whether we should run a piece of code on the CPU or the GPU. In that case, we could set CPU and GPU as our y values, and pick values for x which describe the programs we are compiling. For example, the number of instructions in the program, the density of arithmetic operations, or the size of the dataset that the programs operate on. The idea is that what we’re aiming to build something which looks like this:

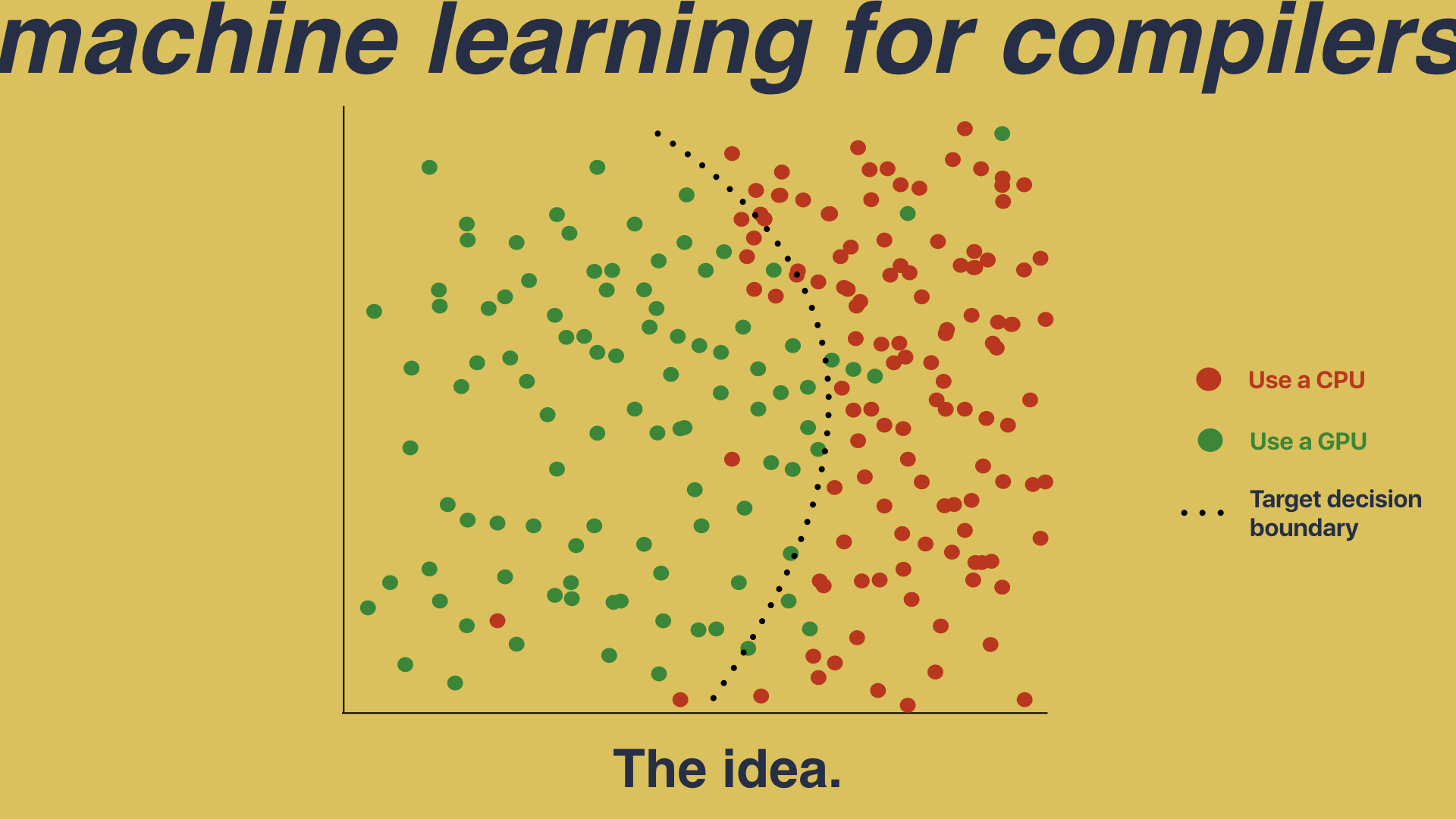

We have a feature space, which captures the properties describing programs; and we have hundreds and hundreds of dots, where each one of those dots is a program which we have run on both the CPU and the GPU in order to determine which one is faster. That’s the idea is that we’re going to take these hundreds and hundreds of dots and learn a decision boundary so that, when a new program comes in, we simply have to map it into this feature space and that will tell us whether we should run it on the CPU or GPU. So that’s the idea of using machine learning to build compiler heuristics. Unfortunately, the reality is a little closer to this:

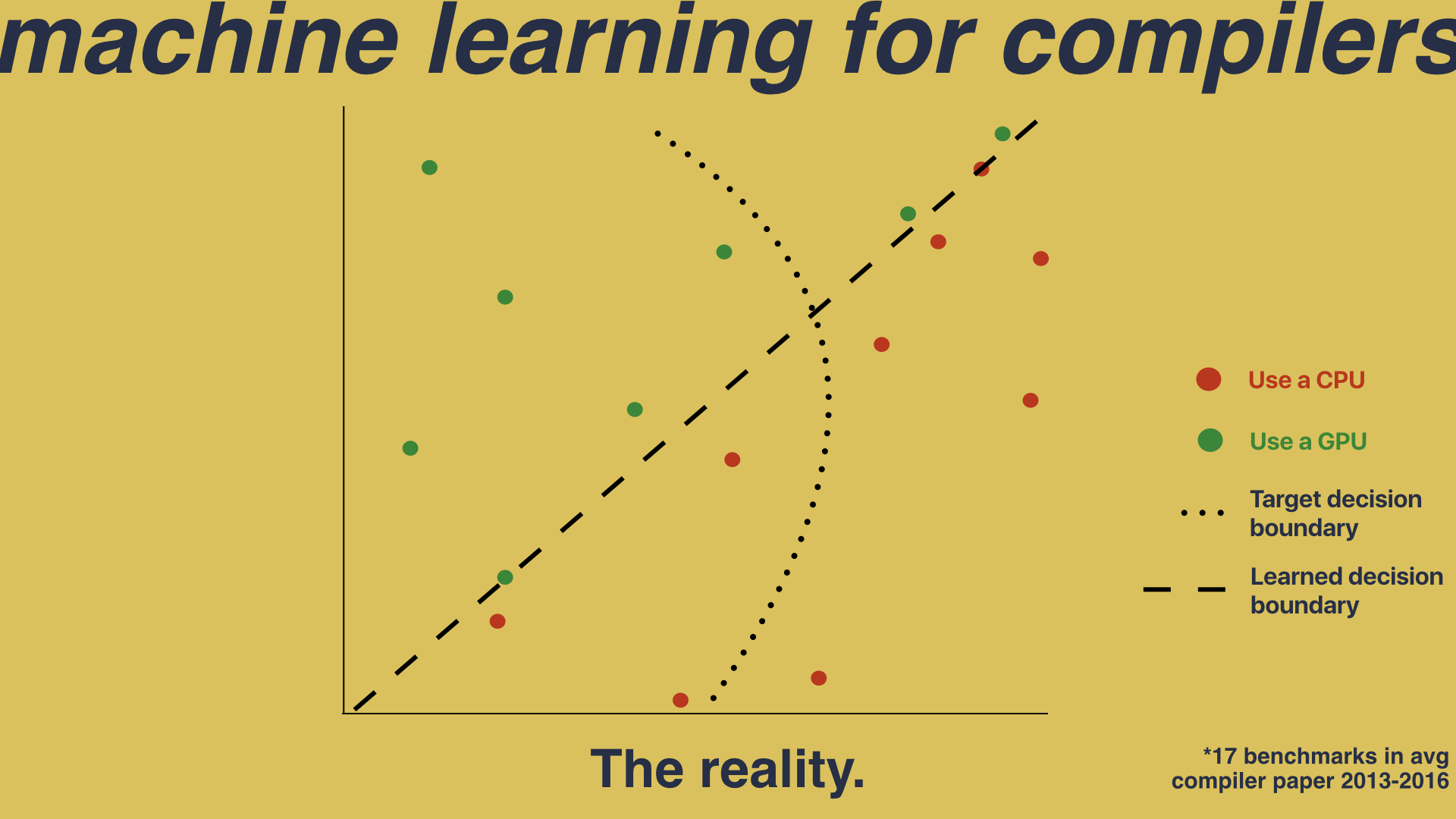

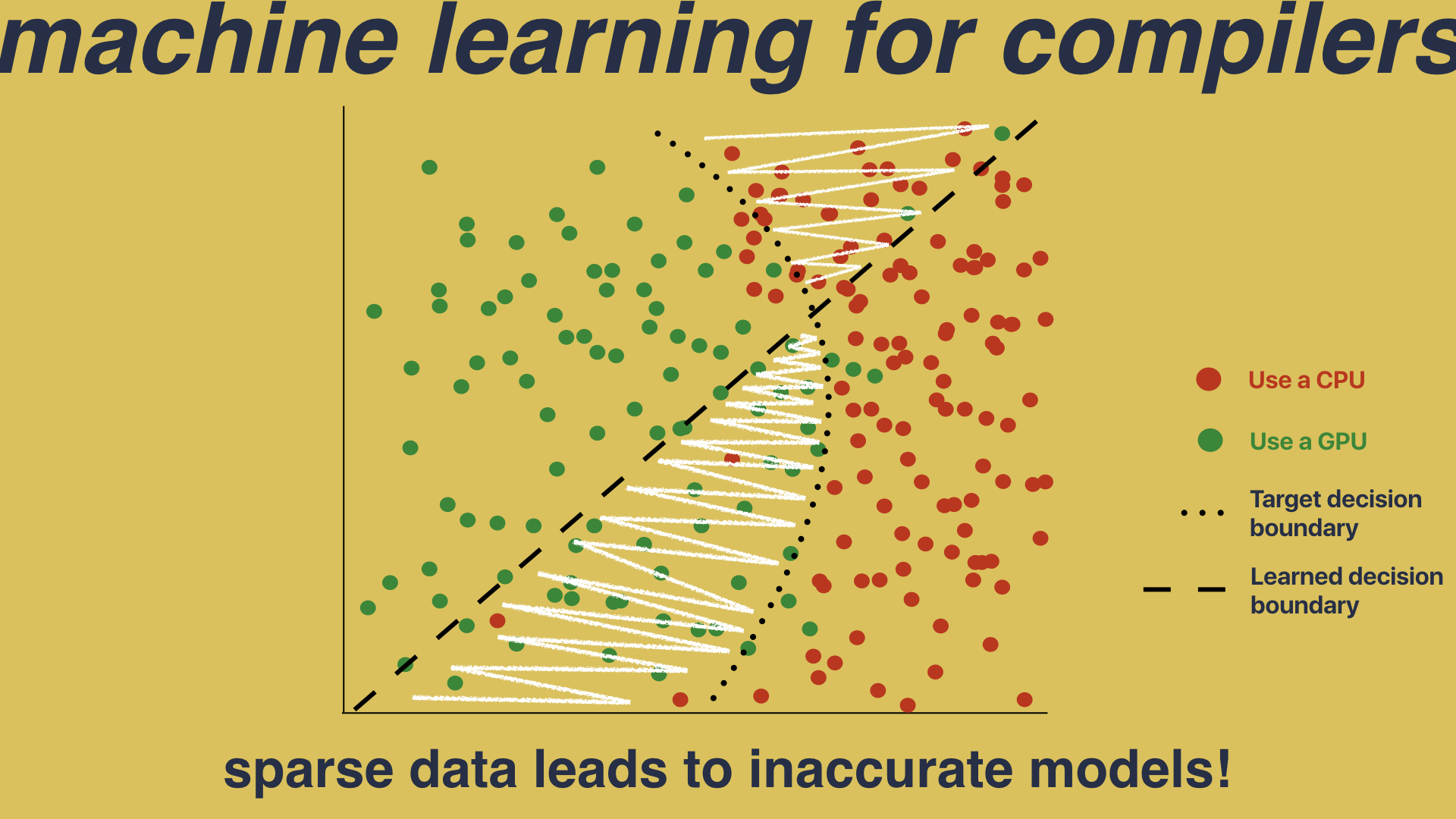

In reality, we don’t have hundreds and hundreds of dots. We instead have a very small number of programs - which we call benchmarks - and the hope that is that these few benchmarks are representative of the entire program space. This is a big problem. When you have sparse data in a high dimensional space, you’re going to miss valuable information:

In this example we can learn a simple straight line decision boundary which gives us great, near perfect results on this handful of programs, but doesn’t capture the complexity of the true space. It isn’t until you deploy the system in to the real world that you see how far from the truth we’ve deviated.

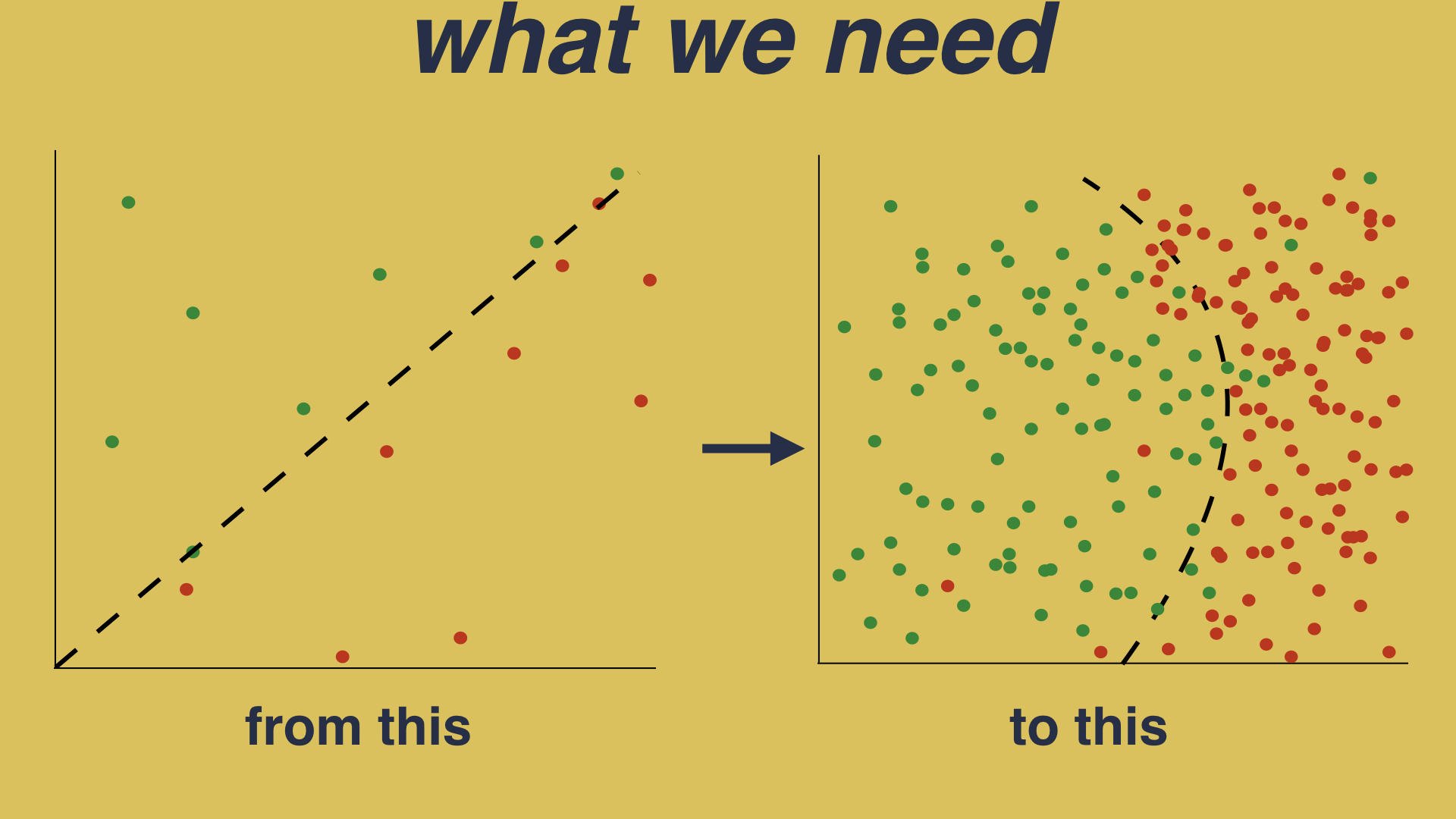

To solve this problem what we need is a way of going from this - which is an inaccurate model built on sparse data - to this - which is a more complete exploration of the program space, allowing for a more accurate model:

To do this we’re going to need a way of enumerating the space of programs. This is the problem that we tackled in the first paper I’m going to talk about. We had a three step approach:

First, we mined code from the web. We exploited the fact that sites like GitHub give access to researchers to millions of lines of real, handwritten code, and we used that to build up a corpus of handwritten code on a scale unprecedented in compiler research.

We then used deep neural networks to model the source distribution. So what we’re doing here is trying to learn the program space - not just the syntax and semantics of a programming language, but what programming language features are most popular, which constructs are most frequently used, and what are the typical characteristics that make up real programs.

We’re building a distribution over the source code, so that once we’ve learned this distribution, we can sample from it to generate as many new programs as we want, knowing that our generated programs are representative of real handwritten code.

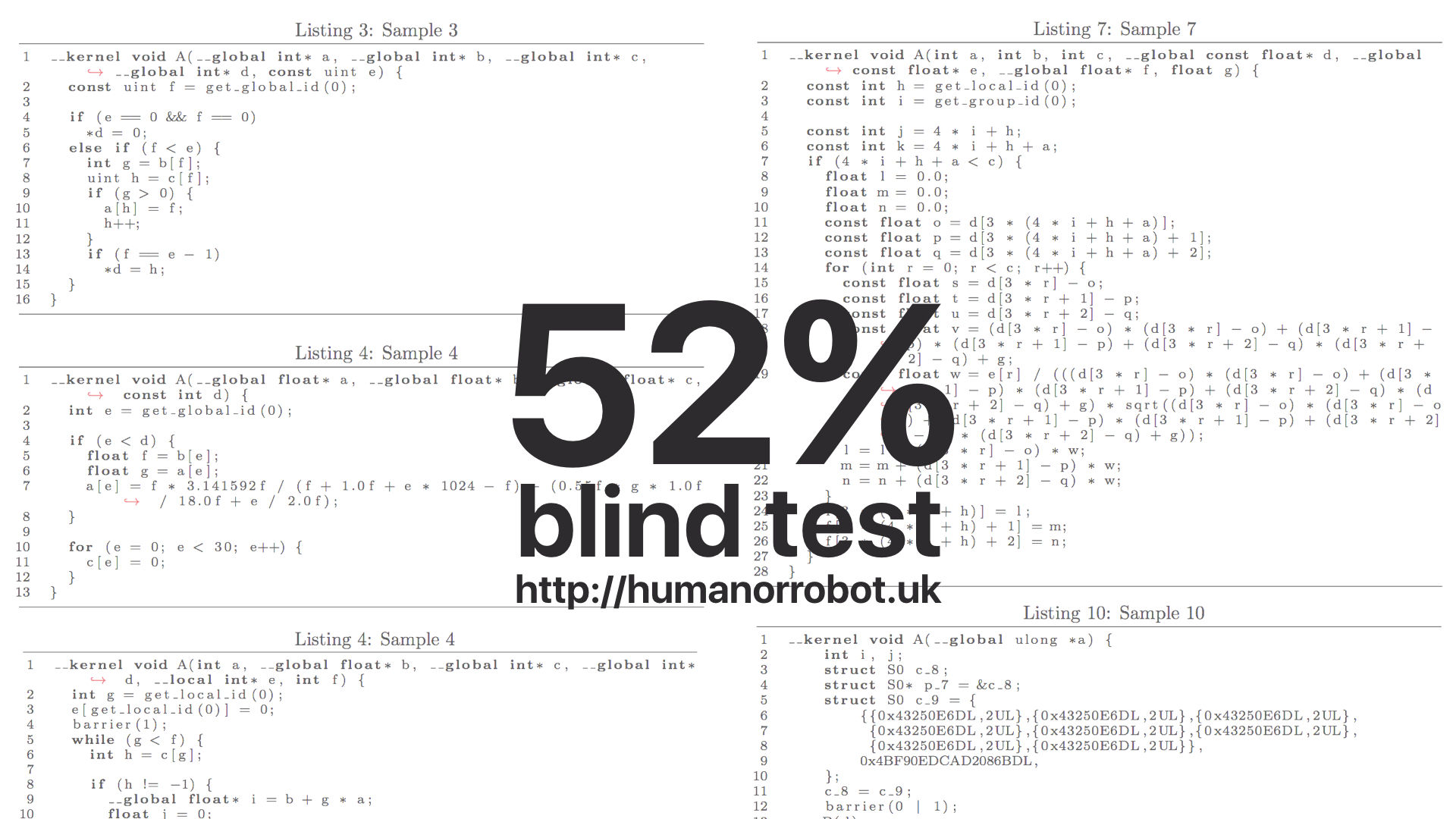

What we found was that, using neural networks trained on GitHub, we are able to generate valid, executable program code which is indistinguishable from real hand written programs. We tested this using a Turing Test: we asked professional programmers to predict whether unlabeled code samples were from man or machine, finding that human experts were no better at distinguishing our code from handwritten than simply tossing a coin.

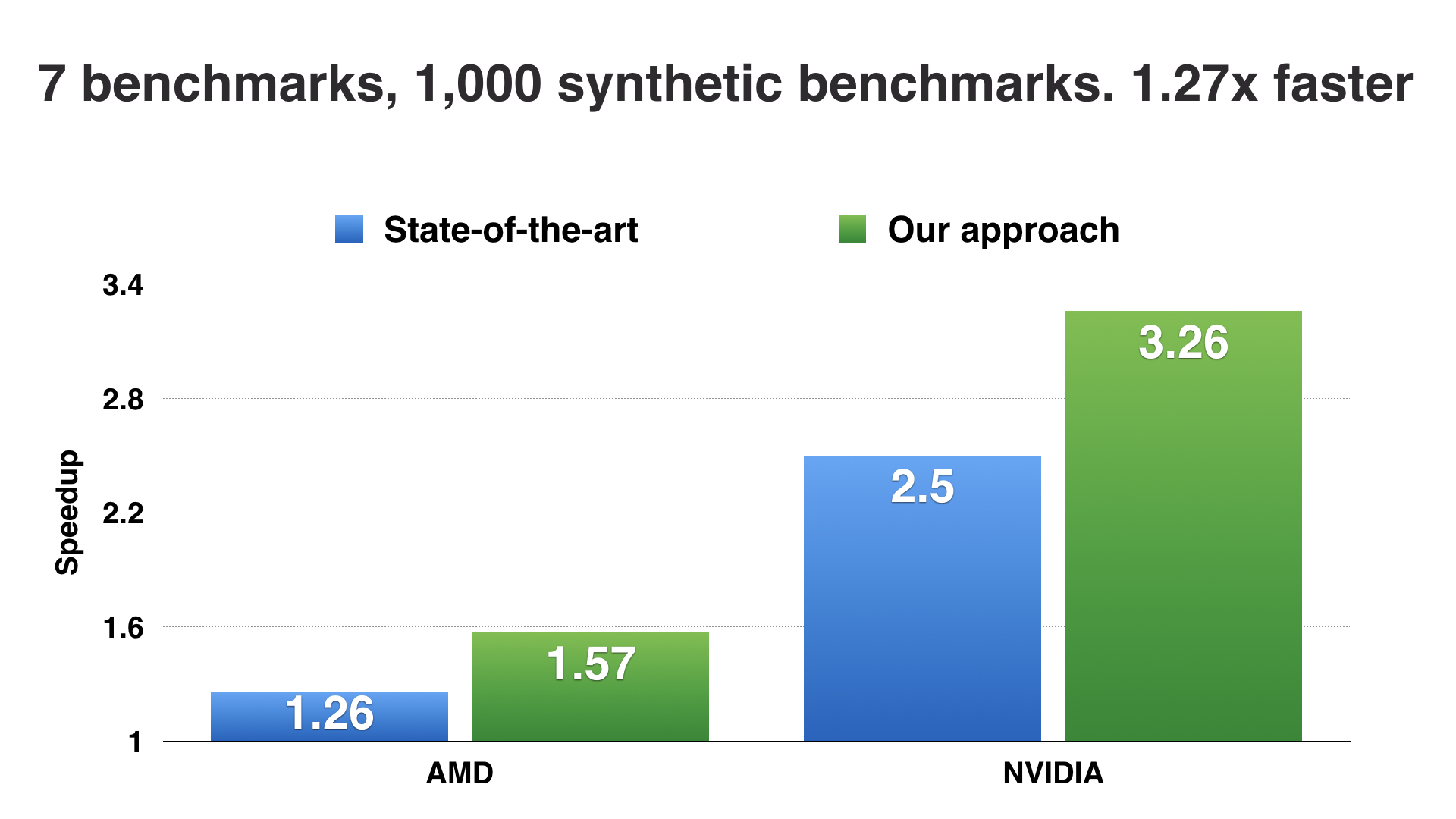

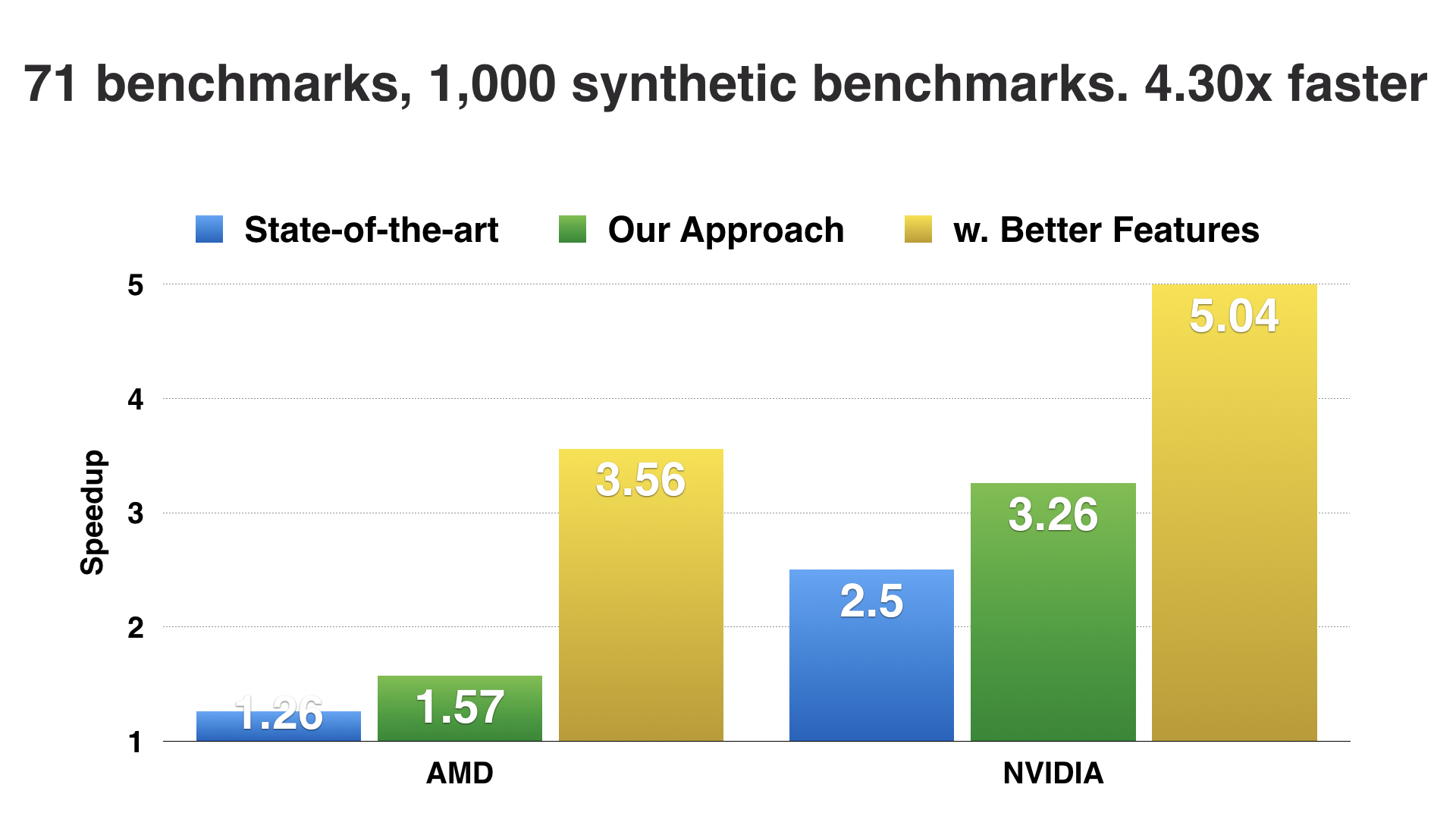

Secondly, we found that using our generated programs, we were able to mitigate the data sparsity problem and automatically improve the performance of a state of the art machine learning heuristic. This was a nice, positive result, but when we looked in detail at the results we found that there were specific cases where, by building a model with more data, the model performed worse. Now this is an incredibly suspicious outcome - why would more data lead to a model making a worse decision? What we found was that, our approach was automatically exposing weaknesses in the design of their model which, when we corrected, led to further, massive performance improvements.

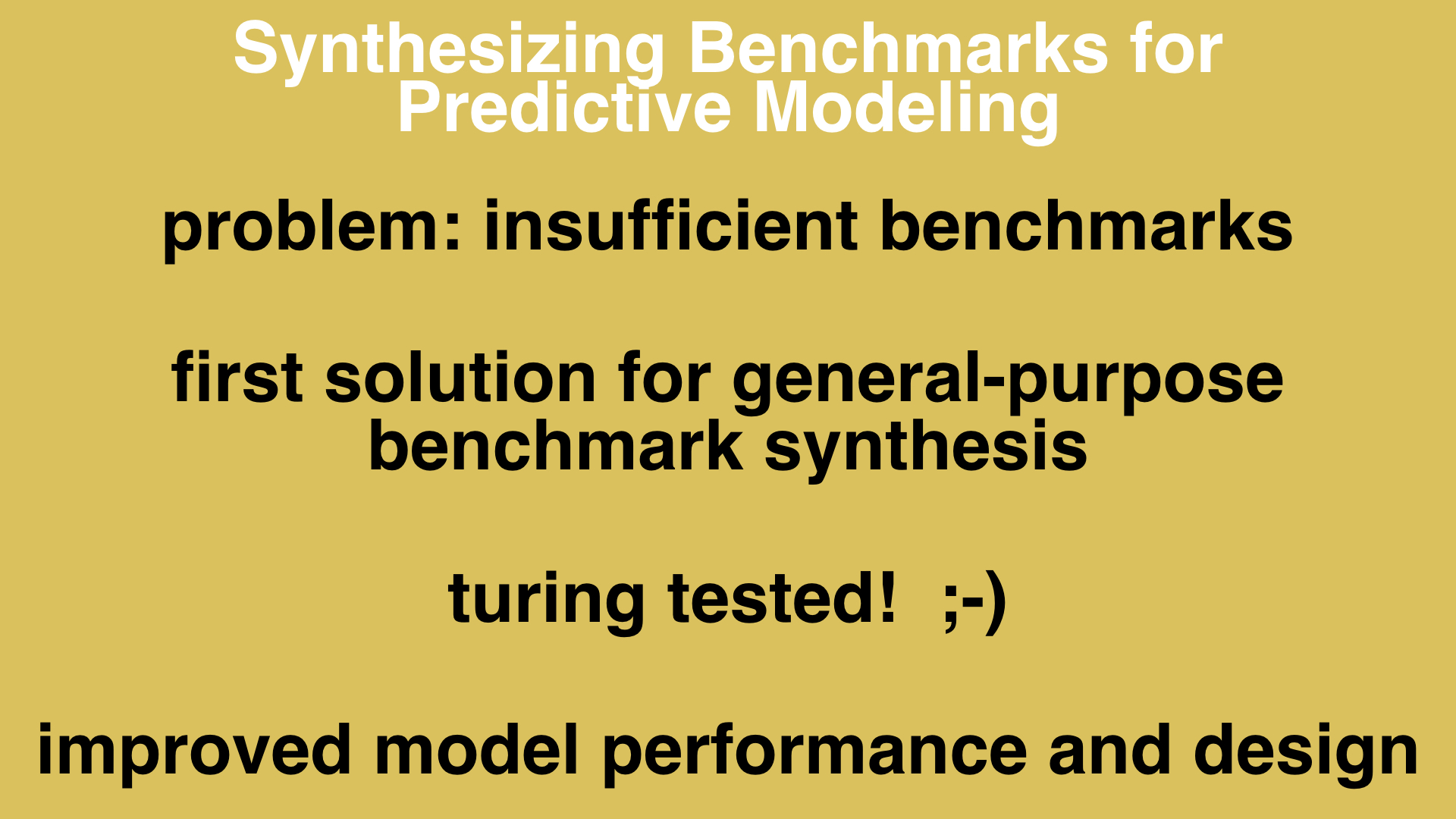

So that is a quick overview of a paper we presented this year at CGO in Austin. The problem we were tackling was that, typically in compiler research, we do not have sufficient benchmarks to reason sensibly about how to optimize code. By applying deep learning over massive codebases mined from GitHub, we were able to offer the first, general purpose solution for benchmark synthesis, and in doing so, were able to generate code of such a quality that human experts cannot distinguish it from handwritten code. Using our generated code, we automatically improve the performance of predictive models, and show how we can use these to further improve the design of the models themselves.

To introduce the second paper, we need to go back to the introduction:

I said that what we’re aiming to do is build a feature space and then learn a decision boundary within it. I glossed over a pretty significant detail - what exactly are those features? Well it turns out that designing good features is an incredibly difficult task.

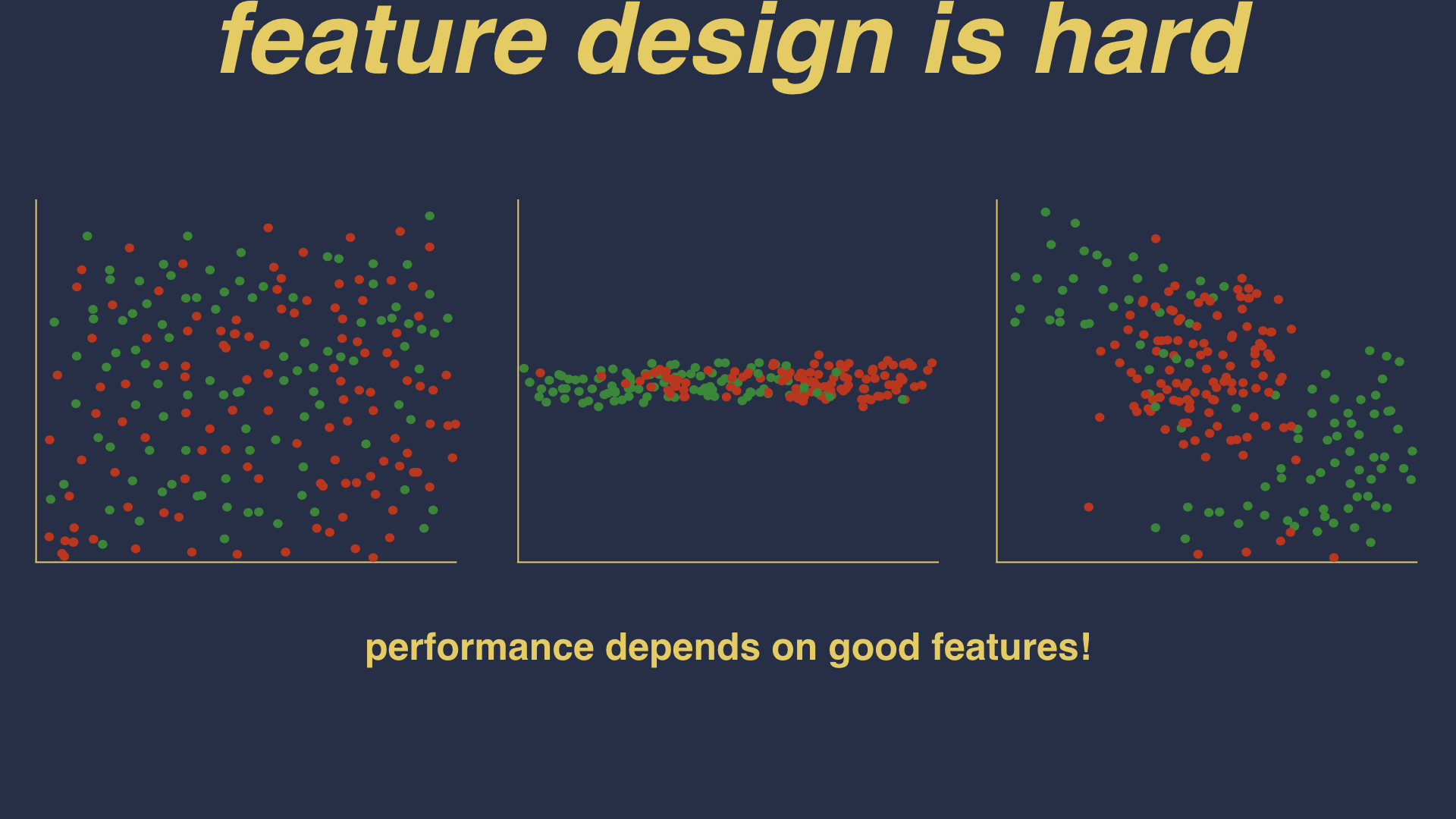

If you pick the wrong features, you could end up with a jumbled mess of a feature space in which no sensible heuristic can be derived. Or maybe you are missing a feature, and you aren’t able to describe the variance within programs. Or maybe you have the right features, but you need to perform some sort of transformation to the space in order to expose the differences between programs.

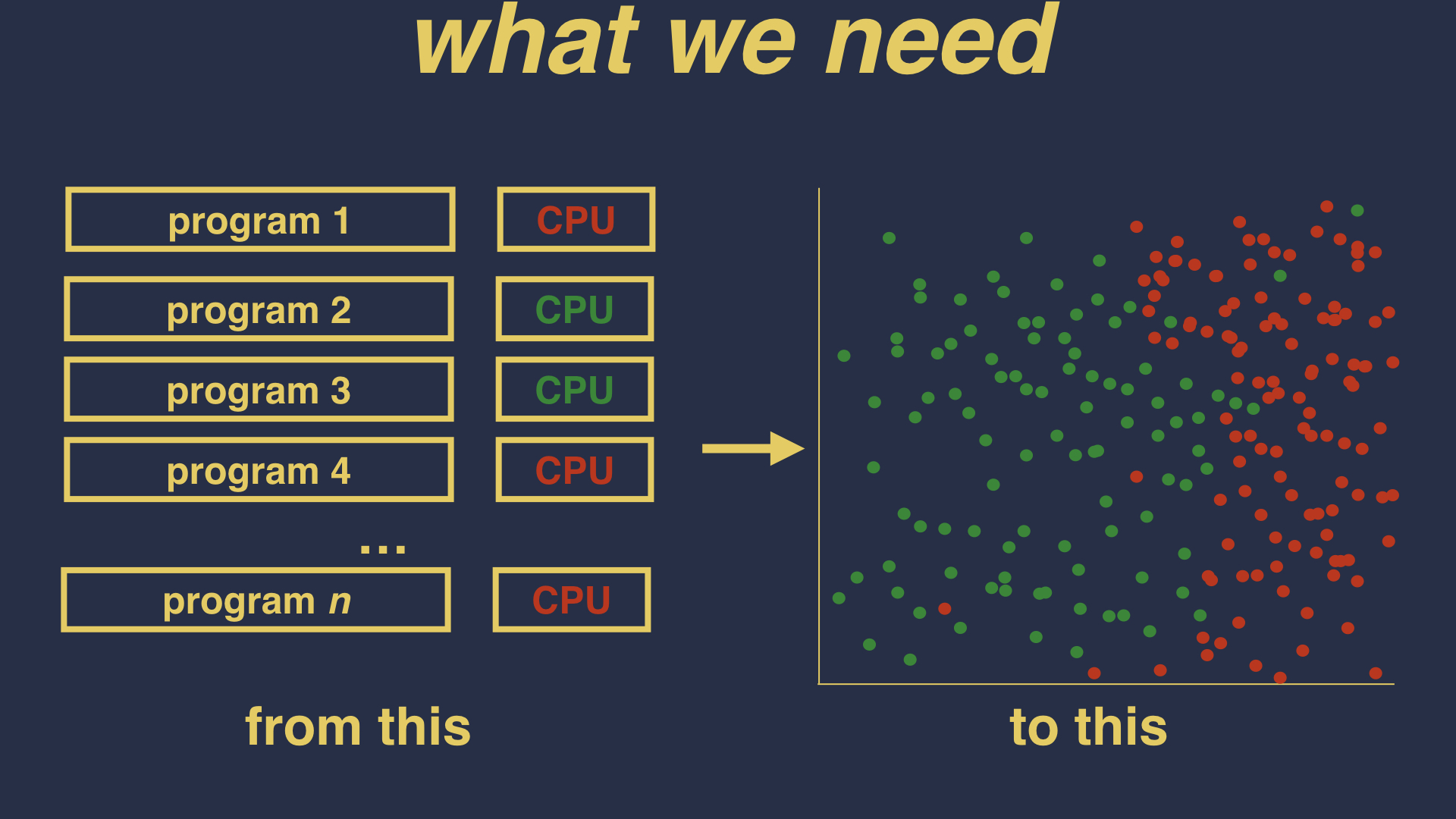

To solve this problem, we ideally need a way of automatically going from this - raw programs and the optimizations which suit them best - to this - a neatly mapped feature space in which we can learn a successful decision boundary. This is the problem that we tackled in this second paper.

We knew from the last paper that, using deep neural networks, it is possible to infer a programming language to a sufficient degree as to be able to generate programs. What’s the next step? What if we could extend the role of the neural net so that, rather than just learning what programs look like, they could learn directly how to optimize the code?

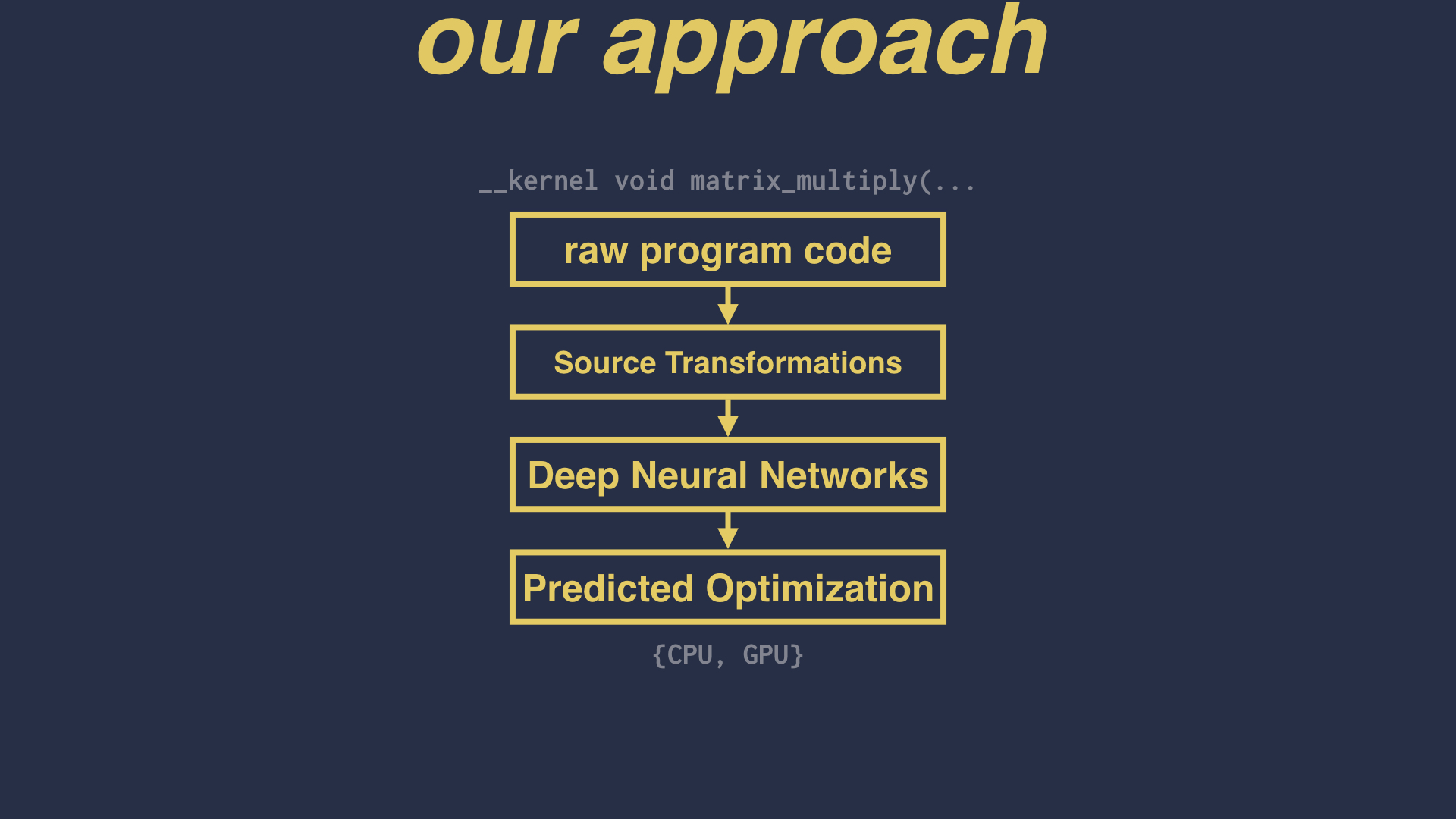

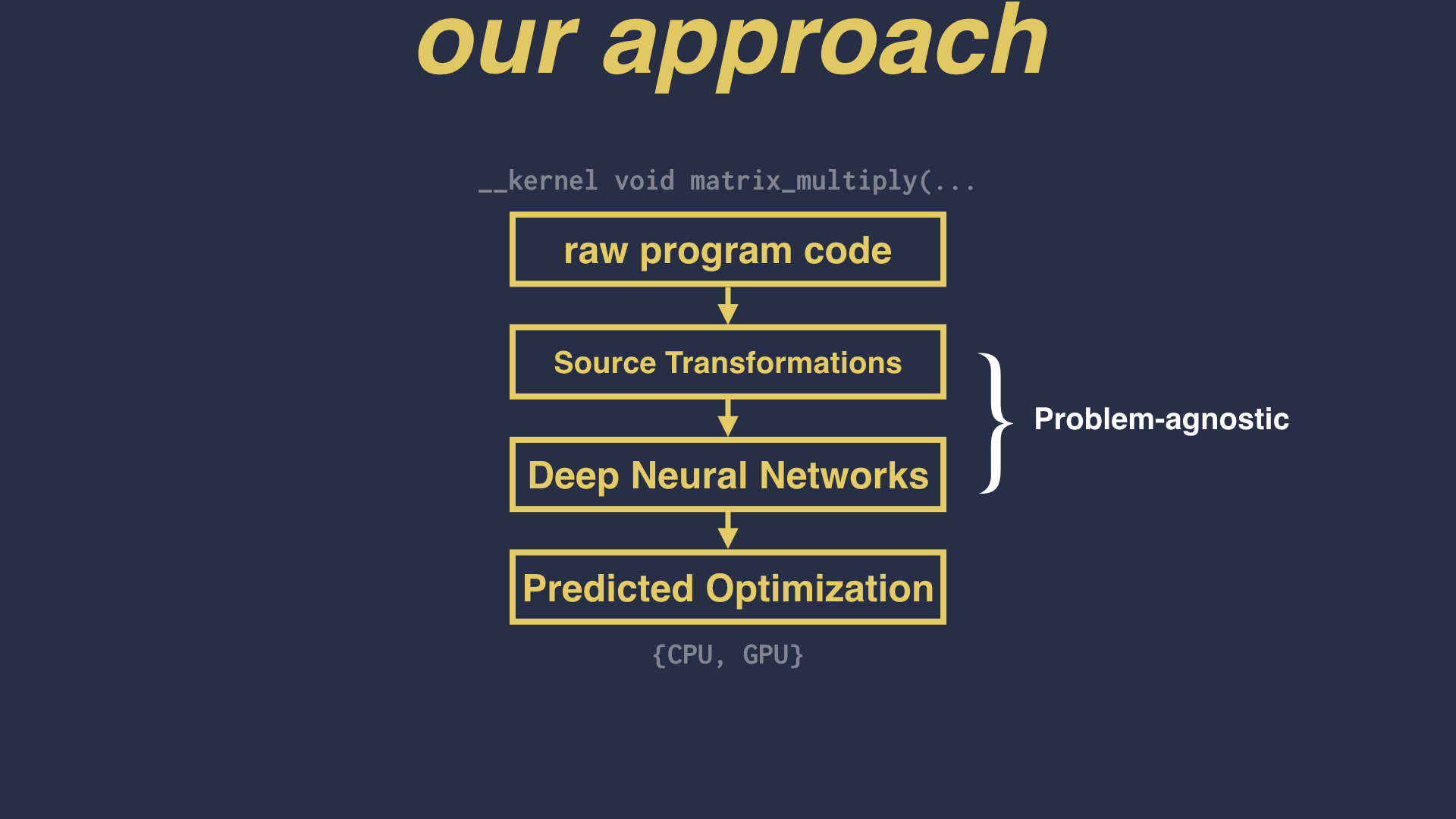

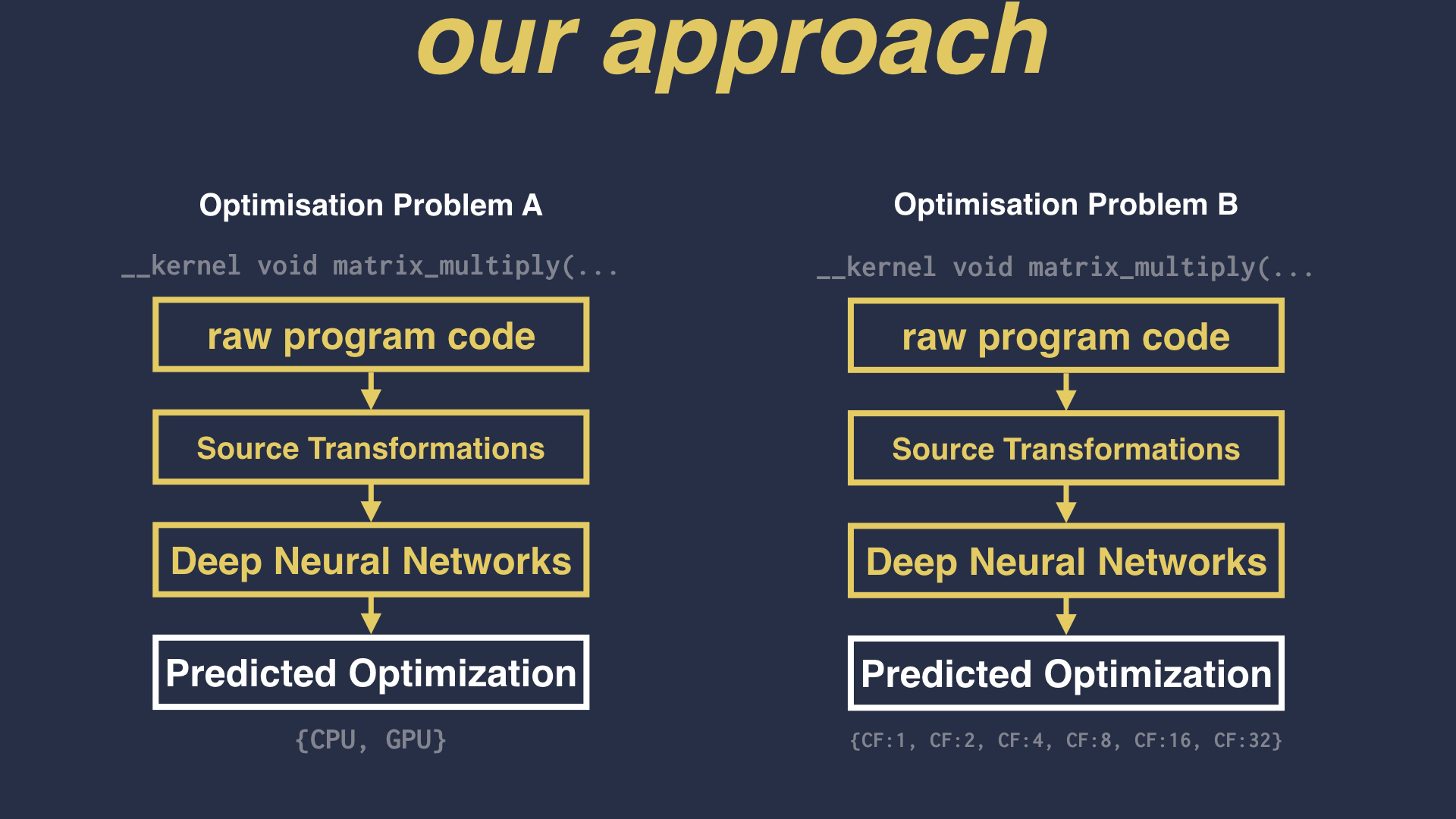

To test this we devised a new system for building a compiler heuristic, in which the program code itself is fed straight into a set of neural networks, and the neural networks directly predict the optimization which should be applied. This completely bypasses the role of feature design.

We realized that, in removing the domain-specific feature extraction role, we had created a generalized approach to learning compiler heuristics. When you have a generalized approach, you can apply the same approach to multiple different problems. In our case, we could use the same neural network design to learn different compiler heuristics simply by changing the learning goal of the model. To test this, we took two state-of-the-art machine learning heuristics, and using the same programs, tested our featureless approach:

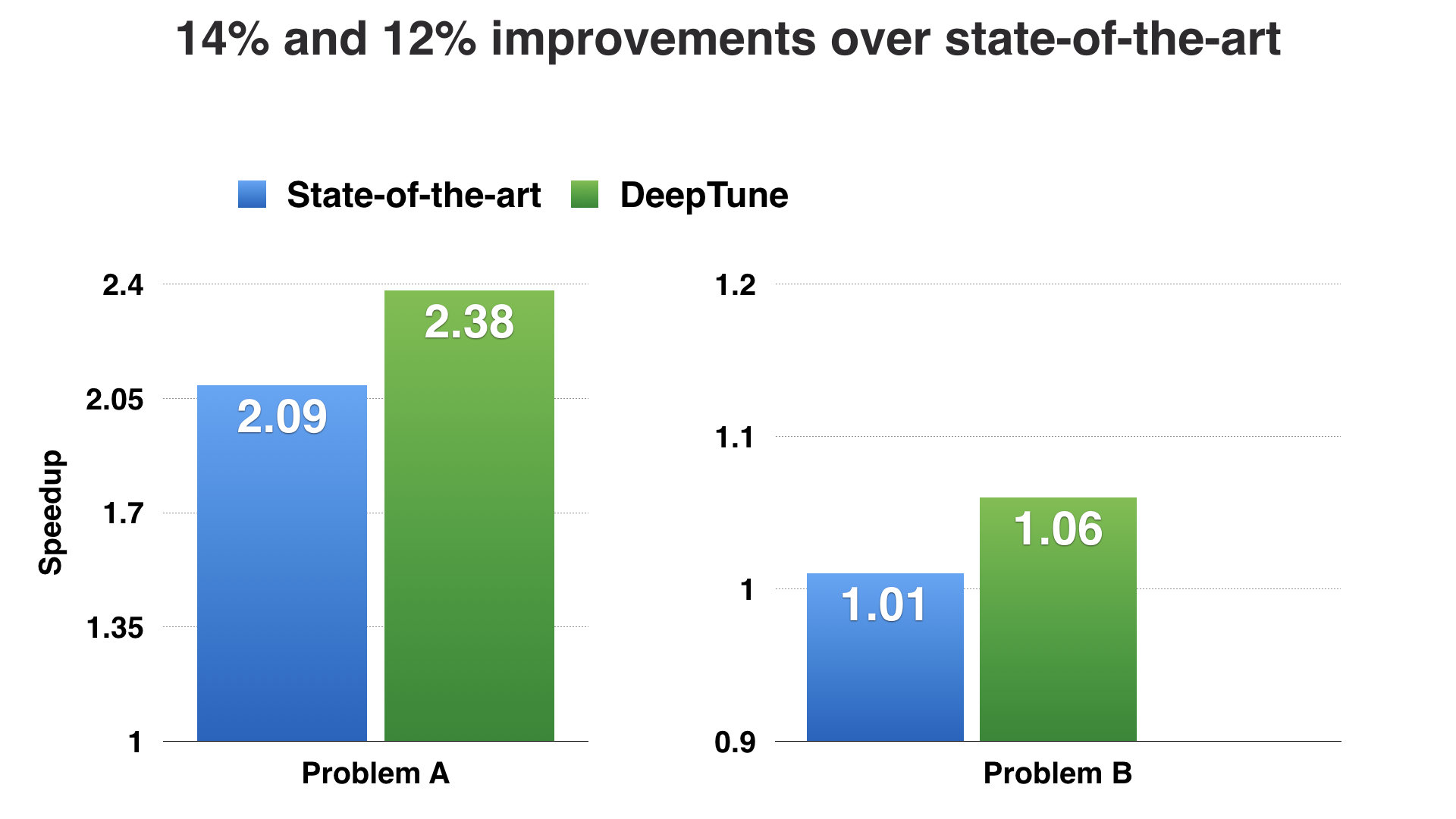

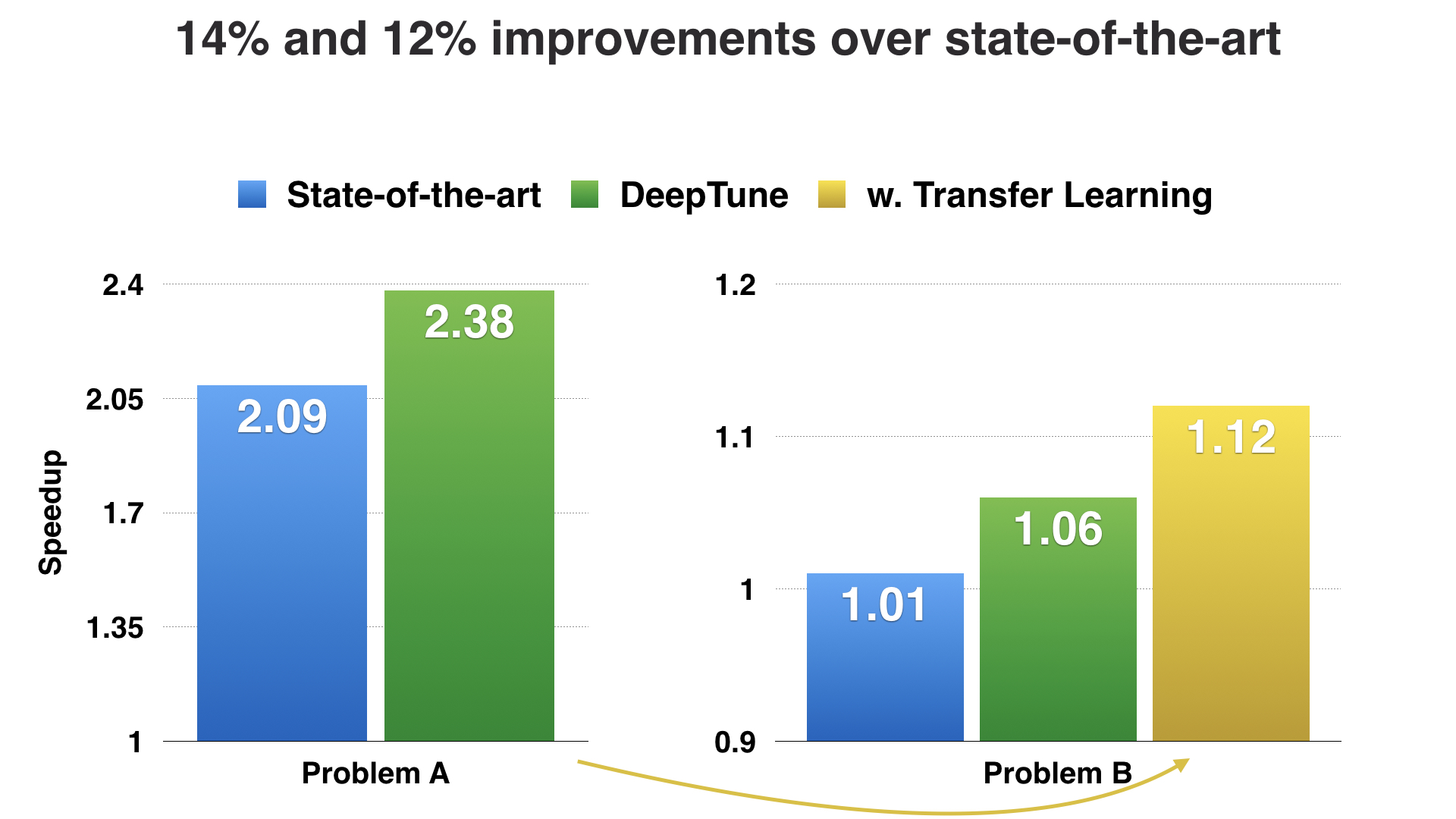

We found that in both cases, we were able to match and even exceed the performance of the expert designed state-of-the-art heuristics, entirely without using code features. In fact, because we were using the same neural network design for the two different problems, we were able to use a machine learning technique called Transfer Learning to, in effect, perform compound learning by taking the information learned from one problem, and transferring it over to the new problem. Doing so further improved the model performance.

So that is a brief overview of the paper I will be presenting in PACT this September in Portland. We tackle the problem that designing features for compiler heuristics is a hard problem. By learning directly over raw program code, we are able to perform “featureless” heuristic learning, using a generic approach for different heuristics. We show that we can outperform state-of-the-art solutions which have been expert designed, and for the first time, are able to transfer knowledge from one optimization problem to another, even the problems themselves are entirely dissimilar.

Hopefully that’s given a quick taste for the kind of problems I’m interested in solving. Thank you for reading!